There was more distance between Part I (linked in case you missed it—start there if you haven’t read it) of this deep dive into John Calipari’s offensive philosophy and today’s Part II than I had intended. Sorry if it felt like waiting on Blond after loving Channel Orange. Here’s hoping this is not a Frank Ocean level of disappointment. Without further adieu, let’s dive in.

The second option in Calipari’s dribble-drive offense

You’ll recall from Part I that player empowerment is the crux of Calipari’s offense. Coach Cal likes to literally and figuratively put the ball in his players' hands. Their duty is to deliver by reading and reacting to what the defense is doing in front of them, with a more specific first objective being pressure on the rim.

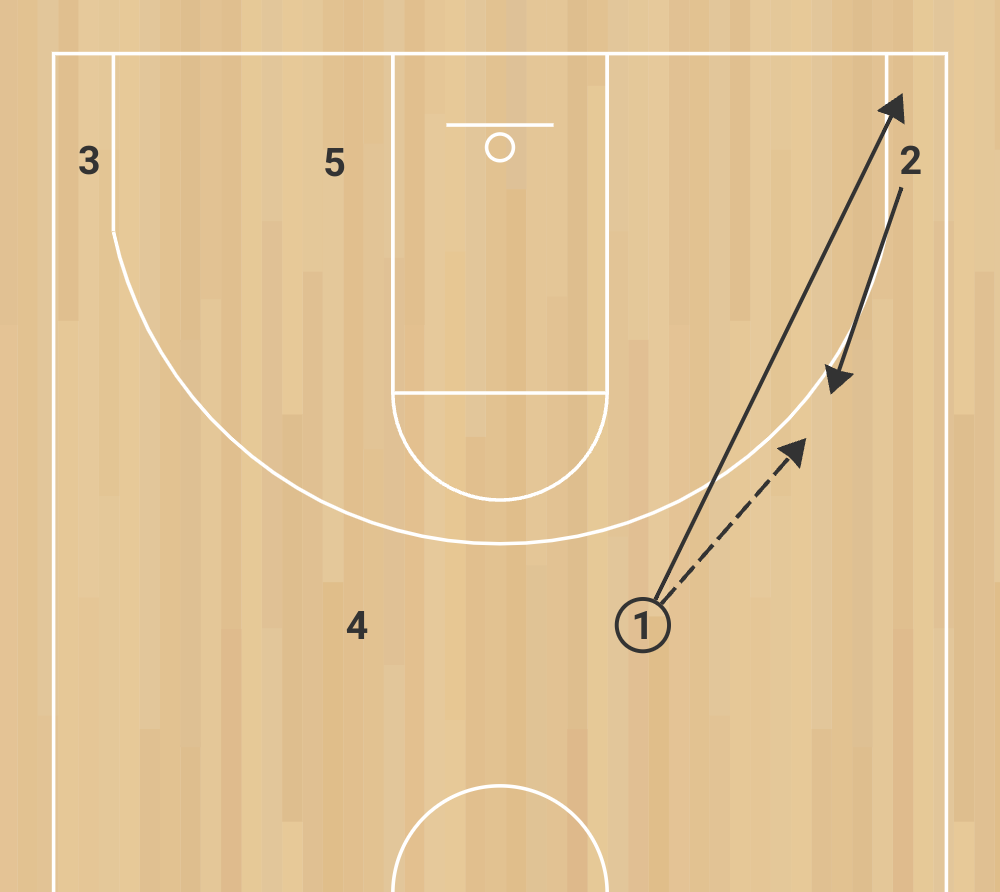

If the first option, top penetration, is unavailable based on what the defense allows, the second progression is to apply that rim pressure from the wing instead of the slot. If the ballhandler in the slot is unable to dribble penetrate, the player from the strongside corner cuts to the wing. The ballhandler passes to the player on the wing and backfills to the recently vacated corner.

That leaves you with an alignment that looks like this:

Middle Drive

The plan now becomes very similar to option one. The ballhandler on the wing will attack the middle of the lane, looking to score at or near the rim. Here is an example of Reed Sheppard driving middle with an additional DHO wrinkle on the wing. Sheppard has a wide driving lane because help doesn’t come from the low man on the weakside (Makhi Mitchell in this case), but he misses the floater.

Here is a textbook example of the middle drive from the wing, but you can see how the spacing is off. Having both bigs in the restricted area causes congestion, forcing Antonio Reeves into a more difficult shot. It’s former Wildcat future Hog Zvonimir Ivisic who is out of position.

The ballhandler could also pass to the five-man off the middle drive if the player guarding him helps stop the dribble penetration:

Here’s a fun middle drive wrinkle: The player in the strongside slot (Reeves) backcuts to the weakside block, and Sheppard dishes to him instead of the low big.

Players can also fold in a pick-and-roll wrinkle to that middle drive:

Given that this is a motion offense, the players along the perimeter must keep moving behind the middle drive to ensure large passing lanes that act as a release valve for that ballhandler. Those release valves can be used as a kick out to a shooter or as a reset to the motion offense.

Baseline Drive

Things look virtually the same if a player drives baseline rather than middle. Along the perimeter, the players move to keep wide passing lanes available to the ballhandler.

The only major difference is that the five-man must cut toward the middle on a baseline drive to keep his passing line open. That looks something like this:

It’s a subtle shift, but Kentucky’s Ugonna Onyenso relocates to the restricted area as Reeves dribbles baseline. Reeves didn’t need to end up dishing the ball, as he converted a ridiculous reverse layup.

Just like in all the other options, players also have to stay spaced for large passing lanes. In this example, Sheppard drives a well-defended baseline but has a sizeable passing lane to find future Razorback D.J. Wagner for a corner three. Wagner doesn’t convert, but this is a great shot opportunity. I also left this final clip long to show how the offense progresses through player movement.

We’ll have one more part of this trilogy to explore where isolation opportunities lie in the dribble drive motion offense.